|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prefer a .pdf? Click here.

|

|

|

Renaming the “John Martin House and Mill”

|

|

|

|

by Harry G. Enoch

Introduction

Located in the Lower Howard’s Creek Nature & Heritage Preserve (hereafter called the “Preserve”) are the ruins of two historic landmarks. According to Clark County historian Kathryn Owen, these landmarks, which she referred to as the John Martin House and the John Martin Mill, were erected in the late 1780s. The sites were placed on the National Register of Historic Places under Martin’s name. Recent evidence shows that these stone structures were erected several decades later—by Jonathan Bush in the 1806-1812 timeframe. The time has come to rename these landmarks.1

The purpose of this article is to review the historical records concerning the house and mill, to explain why, in the 1970s, they were designated as the work of John Martin, and to lay out the evidence proving that they were actually built by Jonathan Bush.

Early Names of the Mill and House

Over the course of time, the mill ruins and stone house in the Preserve have been called by the names of their various owners. In the 1850 manufacturers census, the mill was referred to as Jonathan Bush’s flour mill; in 1860 it was William T. Bush’s flour mill. William T. inherited the mill at his father’s death. An 1861 Clark County map shows William T. residing in the house near the mill. He advertised the mill and house for sale in 1858 and again in 1861. The mill was specifically referred to as a Merchant Mill...a stone building three story’s high” “late in possession of Jonathan Bush” and the home as “first rate stone buildings containing 7 large rooms.” Subsequent deeds (1861, 1867, 1891, 1905) refer to the property where Jonathan Bush had operated a water gristmill. In 1892, Robert Moore executed an oil painting of the mill which he inscribed as “Bush’s Mill on Howard’s Lower Creek, Clark Co. Ky.” In the 1920s, Lucien Beckner and George Doyle collaborated on a series of articles in the Winchester Sun called the “Clark County Chronicles.” In this wide-ranging historical record of early Clark County, the authors referred to the mill as the Bush Mill. In his Clark County Tombstone Records (1935), Doyle referred to the “Burying Ground at Old Jonathan Bush Mill on Lower Howard’s Creek.”

The 1870 and 1880 manufacturers censuses show the mill owner as Alexander S. Hampton, and an 1877 map of Clark County shows his residence at the house near the mill. Hampton owned the mill from 1867 to 1891. In his 1938 Master’s thesis, Joe Kendall Neel called it the Hampton Mill.

Some of the older Clark County residents recall it going by the name of Hart’s Mill, another proprietor. Joel T. Hart owned the mill from 1891 until 1905.

None of these early documents or histories refer to a mill or house owned by John Martin. In fact, John Martin was not mentioned in connection with either the mill or the house until the late 1960s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mill ruins (above) and stone house (below) in the Preserve as seen today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How These Landmarks Came To Be Associated with John Martin

Kathryn Owen in her book, Old Homes and Landmarks of Clark County, Kentucky published in 1967, is the first writer who attempted to tie both the house and mill to John Martin. On page 15 she wrote:

Late in the 18th century, on a hill overlooking historic Howard’s Creek, John Martin erected a house of stone construction which is believed to be the oldest house in Clark County. Long referred to as “the old stone house with port holes,”2 its identity has only recently been ascertained… The records of Old Providence Church show that John and Rachel Martin were received into the church by letter…in 1788… They are buried near their home on Lower Howard’s Creek. [italics added]

The only evidence that the house belonged to John Martin is the implication that he and his wife are buried near their home. The article includes a photograph of the old stone house in the Preserve. Later on the same page, she credits John Martin as the builder of the old stone mill:

In the 1780s, John Martin built a massive water grist mill, which stood within sight of his home… The three-story mill was built of Kentucky River marble. Today it is a deserted ruin…

Miss Owen cited a deposition of Ambrose Coffee as evidence for the date of construction of the mill (about 1786) and the builder (John Martin). This deposition will be examined in detail in a later section.

* * *

In her book Old Graveyards of Clark County, Kentucky (1975), Kathryn Owen has an entry for the John Martin cemetery, listing the burial of John Martin (1740-1821) and Rachel Martin (1735-1820). She did not see the marked graves, but states on page 80 that “these stone inscriptions were illegible in 1970. They were copied years ago by Clark County historian, S. J. Conkwright.” She states that the cemetery is located on “Lower Howard’s Creek, Sheely farm.” At the time Miss Owen wrote, the farm where the mill and house were located was owned by Regina S. Shely, who inherited the property at her father’s death in 1961. 3 (John and Rachel Martin’s graves are actually located on a nearby property that was known as the Harry Bush farm at that time.)

As stated above, Miss Owen believed this cemetery to be the one located near the old stone house in the Preserve. Indeed, there is a cemetery about 100 feet south of the house with a number of unmarked graves. She surmised that Rachel Martin was buried in the box tomb, whose tablet had been broken and the pieces long considered illegible. The tablet has now been deciphered and will be discussed in detail in a later section.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photographs of the house (above) and mill (below) taken in the early 1900s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The narrative laid out in this section attempted to explain how the stone ruins in the Preserve came to be named the John Martin House and Mill. The narrative goes something like this (although much of it is incorrect as will be explained later):

- John Martin built a stone mill and house on Lower Howard’s Creek in the late 1780s (incorrect).

- Ambrose Coffee’s deposition (incorrectly quoted) states that John Martin built a mill in the late 1780s, which must be the mill

represented by the 3½ story stone ruins in the Preserve (incorrect).

- Since he built the mill, John Martin must have built and lived in the old stone house, which is also located in the Preserve (incorrect).

- John and Rachel Martin are buried in the cemetery near the old stone house (incorrect).

- John Martin lived in the house until his death and was then buried beside his wife in the cemetery south of the house (incorrect).

This narrative was used on the site forms for the National Register nominations and resulted in the National Park Service listing these places as the “Martin-Holder Bush-Hampton Mill” (Ck-49) and the “Martin House” (Ck-50).4 The only authority cited for these names was Kathryn Owen. The following section will examine the evidence against each of the above claims regarding John Martin’s involvement in these historic structures. Upon further examination, we find each of the above claims completely refuted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Critical Review of the Evidence

John and Rachel Martin came to Clark County carrying letters of dismission from their Baptist church in Fluvanna County, Virginia. On July 14, 1787, they were accepted as members of the Howard’s Creek (Providence) Baptist Church. They probably had arrived in the neighborhood a short time before. John and Rachel settled on Lower Howard’s Creek on property purchased from William Bush.5

According to the conventional telling of the story, John Martin first built a log cabin for his family, then went to work erecting a 3½ story stone flour mill. After the mill was completed, he supposedly put up a stone house, attaching it to the west side of the cabin. Is any of this story true?

Did John Martin Build a 3½ Story Stone Flour Mill? 6

The earliest mill we know of on Lower Howard’s Creek was described by one of its millers, Ambrose Coffee. In 1809, he made the following statement concerning the origin of the mill:

some time in February 1777 we arrived at Boonesborough and there I continued till 1785 or 1786 I moved then out of Boonesborough into Bushes settlement stayed there a year or two from that there was two of the Martins built a mill on lower Howards creek and there I attended that mill going upon two years and then Colo. Holder bought her and after he bought her I attended her near two years and from that I moved up to the head of spencer creek near old Nicholas Anderson and from that to Slate creek where I now live near Myers mill.7

Note that the deposition does not mention “John Martin,” as stated in Kathryn Owen’s transcription. If Coffee left Boonesborough in 1785 or 1786 and stayed at the Bush Settlement one or two years, he would have come to the mill sometime between 1786 and 1788. This would be the timeframe in which the Martins built a mill. These dates also coincide with the arrival of the Martins in Clark County. William, Orson, John Jr. and Valentine Martin came out in 1786.8 Their parents, John Martin Sr. and his wife Rachel, probably arrived late that year or the following year. John Martin and his son Orson, both blacksmiths by occupation,9 could have been the two Martins who “built a mill.” In 1801, Orson built a mill for himself a little ways upstream on Lower Howard’s Creek; however, he had to hire one Daniel McVicar to install the sophisticated machinery necessary for milling flour.10 Could the ruins of the 3½ story stone flour mill located in the Preserve have been the mill two Martins built in the 1786-88 timeframe? This seems highly improbably for several reasons.

The first water-powered mills in Kentucky were a very simple type called “tub mills.” Tub mills were built to make cornmeal from corn. They were small, inexpensive affairs built mostly of wood that took a couple of weeks to finish and did not require the employment of experienced millwrights. They could have been erected by a pair of competent, knowledgeable blacksmiths. Grinding corn by hand was a laborious process, and settlers anxiously awaited the construction of mechanically powered mills in their neighborhoods. The flour mills that succeeded them were much more complicated affairs.

The 3½ story stone flour mill located in the Preserve was of a highly sophisticated design (known as an automated flour mill) developed by Oliver Evans. These mills required four working levels to accommodate all the mechanical equipment associated with the automated processes. Evans was awarded U.S. Patent No. 3 for his automated gristmill in 1791. His plans were not widely adopted until after the turn of the century. Thus, it is highly unlikely that the stone flour mill in the Preserve could have been erected by the Martins in the 1786-88 timeframe.

Several other lines of evidence argue against the Martins building a flour mill. While corn mills ground meal for local residents, flour mills manufactured a product for export. There was no local market for the large quantities of flour produced by these mills. At these merchant mills, flour was packed into barrels, hauled on wagon roads to warehouses located along the Kentucky River, loaded onto flatboats and shipped to markets in Natchez and New Orleans. Commerce on the Ohio-Mississippi Rivers did not begin until after James Wilkinson took a boat load of tobacco, hams and butter to New Orleans in 1787. In 1786-88, there was no wagon road, no warehouse and no flatboats.

Where Was the Martin-Holder Mill Located?

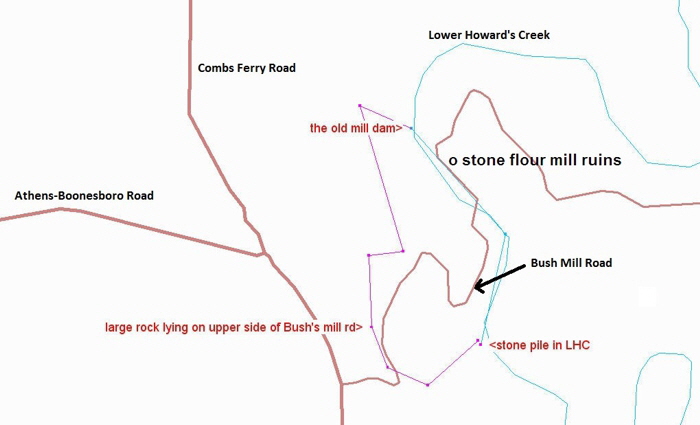

Assuming two Martins did build a mill in 1786-88, it may have been a small corn grinding tub mill. It could have been located near the present stone mill ruins in the Preserve. In fact, there was an earlier mill near the site. An 1829 deed for land along the creek mentions an “old mill dam.”11 After mapping this deed (below), we see that the old mill dam was very near the stone flour mill ruins. This dam could have been the site of the Martin-Holder mill. The mill would have been in the floodplain and would have been destroyed eventually by the creek flooding. No remnants of the mill or dam have been found.

In summary, evidence suggests the following sequence of events. Two Martins, possibly John Sr. and his son Orson, built a small mill on John Holder’s land (1786-88). Holder bought the mill (1788-90) and Ambrose Coffee ran it for several years. This mill, which I will refer to as the Martin-Holder mill, may have ground corn for settlers in the creek valley and perhaps also for a distillery. The Martin-Holder mill was probably located at a site referred to in the above-mentioned deed as the “old mill dam” on Lower Howard’s Creek, not far from where the 3½ story stone flour mill was later erected.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The “old mill dam” mentioned in an 1829 deed stood very close to where the stone flour mill was later erected.

|

|

|

|

Where Was John Martin’s House?

No direct evidence identifies John Martin as the builder or owner of the old stone house located in the Preserve. Indirect support came from the belief (1) that John Martin built the nearby stone flour mill and (2) that he and his wife are buried in the cemetery near the house. Evidence cited in the previous section indicates that John Martin was not the builder of the 3½ story stone flour mill. It turns out the Martins were not buried in the cemetery near the house or anywhere on the Preserve. Their graves were found on a neighboring farm more than a half a mile away.

Several years ago, Clare Sipple and I went in search of the grave of Hannah Hinde, whose third husband was Valentine Martin, a son of John Martin. We found her grave and handsome tablet on the Merrill Bush farm. The adjoining grave with a missing tablet is the probable burial place of Valentine. To our surprise, we found the grave of John Martin’s wife Rachel in the same cemetery. The crudely formed inscription appears to read

In Memory Of Rachel Martin

Born February 20, 1735

Who Departed This Life January 26, 1820

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Left) Rachel Martin grave, tall stone, beside an unmarked gravestone that may be John Martin’s. (Right) Rachel Martin’s barely legible inscription.

|

|

|

|

To the left of Rachel’s gravestone, and nearly matching hers, is a stone whose inscription is completely worn away. As the husband and wife were reportedly buried beside each other, this is likely the grave of Rachel’s husband, John Martin. This creates a serious conflict with the stories that associate the Martins with the stone house in the Preserve. This finding prompted an examination of the deed record to find out exactly where John Martin’s farm was located. The deed evidence indicates that Martin never owned the land where the stone house stands in the Preserve.

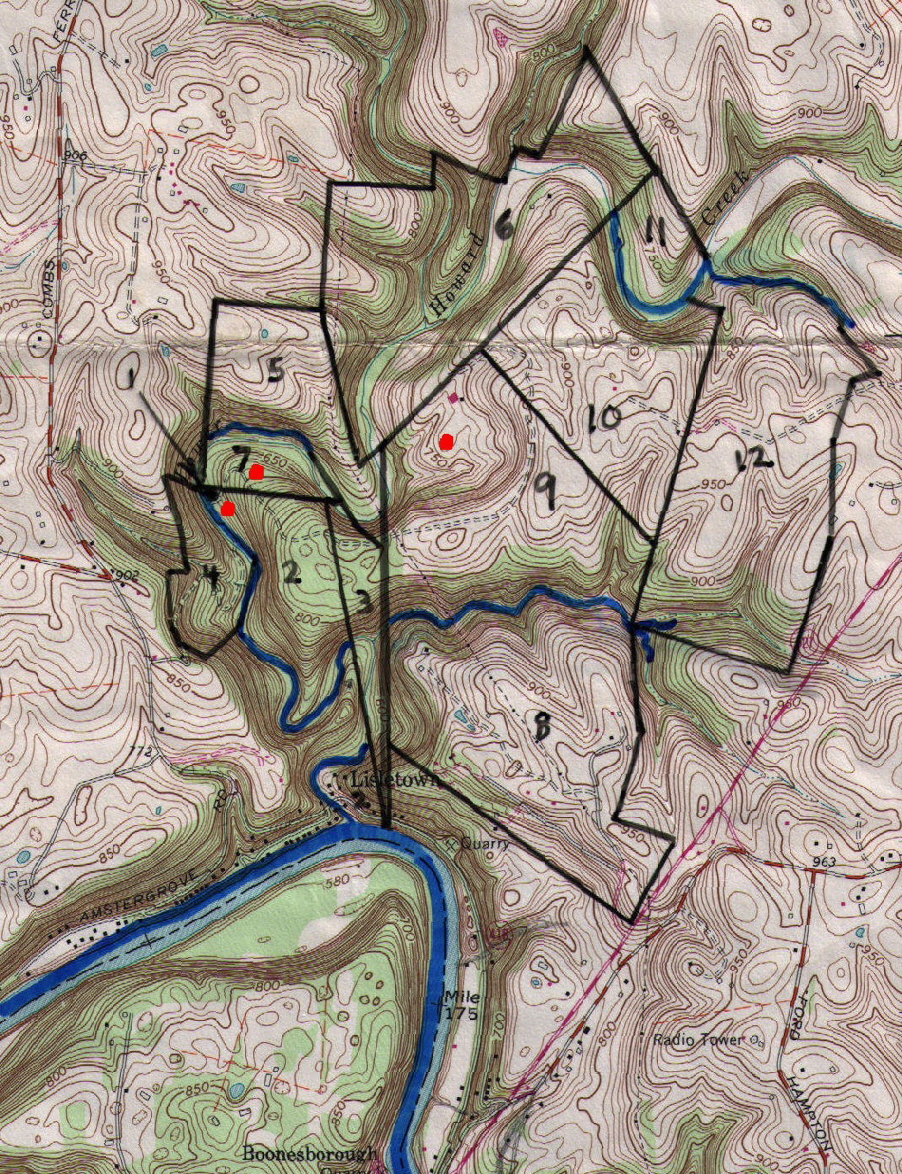

After settling in Clark County, John Martin purchased a tract of approximately 250 acres from William Bush.12 This is the only land Martin ever owned in the county. On the map below, this land is shown as two parcels: #9 & #10. The land was bordered by Deep Branch on the south and by Lower Howard’s Creek on the northern tip. John’s son William Martin bought 122 acres from William Bush, tract #8. His farm, bordering his father’s, was south of Deep Branch.13

In 1808, John and Rachel Martin sold part of their homeplace (tract #9) to their son Valentine.14 They probably lived there with Valentine in their later years. They were buried in the small family cemetery, where Valentine and his wife Hannah were interred later. This cemetery is located on tract #9, shown by the red dot on the deed map below. There is a handsome old springhouse nearby, walled up with stone. The John Martin home was probably located near the cemetery and spring. It seems likely that John and Rachel Martin lived on this homeplace from the time they first came to Clark County. To reiterate, this farm (tracts #9 and #10) is the only land Martin ever owned in the county.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early land ownership on Lower Howard’s Creek

The 3½ story stone flour mill (erroneously called “John Martin Mill”) is located at the red dot on tract #2. The old stone house (erroneously called the “John Martin House”) is located at the red dot on tract #7. The house and mill are both in the Preserve. John and Rachel Martin lived, died and were buried on tract #9 and owned no part of tracts #2 and #7.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

An old spring near the graveyard that may have served the John Martin homestead

Making the Case for the

Jonathan Bush House and Mill

It seems highly improbable that John Martin would build a log cabin followed by a stone house on land he did not own. One way to identify the builder is to examine the deed evidence. The builder might be identified by determining who owned the land where the house and mill stood. Tracts #3, #5, #6, and #7 were part of an original patent to Charles Morgan,15 a prolific land speculator in early Kentucky. He lived on Boone Creek,16 so Morgan was probably not the builder of the house and mill on Lower Howard’s Creek. Morgan sold tract #7, where the house is located, to Jonathan Bush in 1812.17

We have already shown that the Martin-Holder mill—a small gristmill for grinding corn—was built too early to be the stone flour mill in the Preserve. Jonathan Bush purchased the 3-acre Martin-Holder mill tract in 1806 (#1 on the map above).18 That same year Bush acquired tract #2 of 100 acres, where the stone mill ruins are located.19 With the land ownership cleared up and Jonathan Bush identified as the owner of the land where the house and mill are located, he becomes the obvious candidate for building these two stone structures in the 1806-1812 timeframe.

|

|

|

|

|

Another mystery was solved several years ago when Preserve manager, Clare Sipple, was mowing weeds around the box tomb in the cemetery near the house. A large fragment of the tablet had been standing next to the grave for some time and, on this day, the sun was at an angle that made part of the inscription readable. Probing around the grave turned up more pieces of the tablet, which we cleaned and fit together as best we could (see photos below).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The grave turns out to be the burial place of Diana Emerson Bush, the second wife of Jonathan Bush. In 1935, George Doyle transcribed the tablet, which now can be verified by the pieced together fragments:

In memory of ______ Emerson

Born Feb. 7, 1791 Married to

Jonathan Bush June 2, 1814

Departed this life March 5, 1819

______ Shannon preached her funeral

Nov. 18, 1819 20

Doyle stated that the inscription was followed by “a long description of the qualities and perfections of the deceased, most of which is undecipherable….” Due to weathering of the stone, Doyle misread the “1819” date—Diana died in 1849. 21

Doyle identified the cemetery as the “Burying Ground at Old Jonathan Bush Mill on Lower Howard’s Creek.” It seems logical to assume that Bush would have been living in the house when he buried his wife in the cemetery. Doyle also identified the mill as Jonathan Bush’s. We also know that it was Jonathan Bush who opened the wagon road from the mill to the warehouse on the Kentucky River. In 1807, he petitioned the county court for permission to build the road, which the court finally approved in 1809. The road was to run from the mill,

crossing Howards Creek a little below the mill and near the foot of a hill, passing through the land of said Bush, from thence up the north side of said Hill by several windings to the top, and from there the nearest way to Intersect the Bourbon Road… 22

The Bourbon Road, also called Holder’s Road, ran down the hill to the warehouse and boatyard beside the Kentucky River. This road was absolutely critical to operation of the flour mill. Without Bush’s wagon road, there would have been no practical way to get barrels of flour from the mill to the warehouse. No one would have built an elaborate, expensive flour mill without a road to haul wheat in and haul flour out.23

The Bluegrass Heritage Museum has an oil painting executed by Robert Moore in 1892. On the back of the painting the artist inscribed the following: “Bush’s Mill On Howard’s Lower Creek, Clark Co. Ky.” (see below, right) A 1923 article in the Clark County Chronicles provides additional corroboration for Jonathan Bush being the original builder of the flour mill:

Practically all of these old mills have passed away with the exception of the Bush mill, near the mouth of the creek, which is still standing and of which two fine oil paintings have been presented to the Clark County Historical Society by Captain C. E. Bush, a grandson of the original builder of the present structure. 24

|

|

![]() |

![]() |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oil painting of the Bush Mill from C. E. Bush (left, now at Holly Rood Mansion) and by Robert Moore (right, now at the Bluegrass Heritage Museum)

|

|

|

|

|

It appears that the stone mill had long been called the Bush mill, the builder referred to as the grandfather of C. E. Bush. This was Charles E. Bush, the son of James Simpson Bush,25 who was the son of Jonathan Bush.

As further evidence, we have a letter from Mrs. Anna Bush Coffman, who was a niece of C. E. Bush and the great-granddaughter of Jonathan Bush. She wrote

We visited the old mill in May 1926, is near Boonsboro, Ky, on Howard’s lower creek. Built by our Great Grandfather Jonathan Bush. The first mill was Log, built near 1785 by a Mr. Holady. The old stone homestead is around the driveways to the left of the picture [of the mill].26

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mrs. Anna Bush Coffman photos of the mill (left) and house (right) in 1926

Mrs. Coffman even mentioned a log mill preceding Bush’s. The one she refers to could have been the Bush-Holder mill. Although “Mr. Holady” was not further identified in her letter, a Stephen Holladay came to Kentucky in 1788 from Spotsylvania County, Virginia, after serving in the Revolutionary War. He married Anna Hickman and lived on Boone Creek in Clark County.27 His occupation is uncertain.

There is no question that Jonathan Bush operated the flour mill on Lower Howard’s Creek for many years. The mill was described in some detail in the Clark County manufacturers census of 1850:28

- Owner: Jonathan Bush

- Business: Flour mill

- Capital: $4,000

- Motive power: water

- Raw materials: 3,000 bushels of corn & 3,000 bushels of wheat

- Annual product: 400 barrels of flour & 3,000 bushels of meal

- Annual value: $4,800

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jonathan’s son William T. Bush took over the mill after his father’s death in 1857. William T. put the mill up for sale in 1858. His newspaper advertisement gives a good description of the property:

My Land, lying on Lower Howard’s Creek in Clark county, Ky., containing about 200 acres, on which there is situated a Merchant Mill, with two run of stones with all the appurtenances of a first rate Mill with an over-shot wheel, 20 feet diameter, and first rate dam and race, all in good repair. It will run nine or ten months during the year by water. The Mill is a stone building three story’s high. There are on the place first rate stone buildings containing 7 large fine rooms. There is also on the place a fine Barn and stables.

I will also sell one-third interest in a Copper Distillery, situated within a half mile of the Mill. There is sufficient apparatus connected with it to make six barrels of whiskey per day.

I will also sell to the purchaser of the property, if desired, a Negro Man, who is a first rate Miller. 29

Bush finally succeeded in selling the mill to James McKinney in 1861. The deed described the tract as “recently owned and occupied by said Bush and formerly owned and occupied by his father Jonathan Bush on which is a water Grist Mill.” Successive owners were Alexander S. Hampton (1867), John W. and Joel T. Hart (1891), and Green Parker (1905), and Hubbard L. Stevens (1906). 30 In each of these transactions, the house was conveyed along with the mill. The mill went out of operation in the early 1900s, sometime after Stevens took over. The house, which never had electricity or running water, was occupied until the 1950s.

Conclusion

The above narrative lays out the evidence showing that the 3½ story stone flour mill and nearby stone house in the Lower Howard’s Creek Nature & Heritage Preserve were constructed by Jonathan Bush. In the 1970s, due to several assumptions shown herein to be erroneous, construction of the mill and house were attributed to the work of John Martin. This has caused problems for John Martin descendants who come to the Preserve expecting to view the ancient home and business of their ancestor. Our current reports, trail guides and website now consistently refer to the house and mill as the work of another Clark County pioneer: Jonathan Bush.

Another problem arises from the fact that the John Martin designation appears in the National Register of Historic Places. The Preserve will continue to pursue avenues to convince the National Park Service to change these listings to reflect their historically accurate names.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. In 2011, Lower Howard’s Creek Nature & Heritage Preserve asked the Kentucky Heritage Council to petition the National Park Service for a name change; specifically, to revise the names of the National Register listings to reflect the historical accuracy of these places. A detailed report was submitted to serve as evidence. This article is an abbreviated version of that report. 2 Interestingly, archaeologists, architects and historians examining the house have been unable to find any sign of these “portholes.”

2. Interestingly, archaeologists, architects and historians examining the house have been unable to find any sign of these “portholes.”

3. Clark County Deed Book 165:485.

4. The house and mill were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and 1980, respectively. (Bush and Hampton were assumed to be later owners of the Martin-Holder Mill.) Since that time, unfortunately, these stone ruins in the Preserve have been widely referred to by other writers in numerous history books, newspaper stories, research reports and scholarly articles as the “John Martin House and Mill.” See, for example, Kentucky Heritage Council, Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky: Clark County (1979); R. Gerald Alvey, Kentucky Bluegrass Country (1992); Thomas D. Clark, Clark County, Kentucky: A History (1995); Clifton R. Smith, Lower Howards Creek (2000); Grant Day, et al., “John Martin’s Mill in the Lower Howard’s Creek Valley of Clark County, Kentucky,” The Millstone 2:30 (2003); “DAR Hears History of Lower Howard’s Creek,” Winchester Sun, August 6, 2007; “Lower Howard’s Creek Grant Gains Support,” Winchester Sun, January 30, 2009; J. Eric Thomason, “Lower Howard’s Creek, Kentucky as an Example of Changing Industrial and Consumer Landscapes, the John and Rachel Martin House,” Southeastern Archaeological Conference (2002); R. Berle Clay, et al., “Cultural Resource Survey of Lower Howard’s Creek Heritage Park and State Nature Preserve, Clark County, Kentucky” (2001); Fitzsimons Office of Architecture, Inc., Historic Structures Report: John Martin House (2004) and many others.

5. Clark County Deed Book 1:630.

6. This section is adapted from a more detailed account in Harry G. Enoch’s Colonel John Holder, Boonesborough Defender & Kentucky Entrepreneur (2009).

7. Madison County Deed Book I:95.

8. Obadiah Baber, Revolutionary War pension file, R. 347, VA.

9. Harry G. Enoch, Rise and Fall of Orson Martin, Blacksmith (Winchester, KY, 2013).

10. Ibid., p. 26.

11. Clark County Deed Book 23:463.

12. Clark County Deed Book 1:630.

13. Clark County Deed Book 1:403.

14. Clark County Deed Book 6:231. They sold tract #10 to son Orson. Clark County Deed Book 3:463.

15. Old Virginia Grants Book 4:491.

16. Boone Creek formed the county line between Clark and Fayette.

17. Clark County Deed Book 9:47.

18. Clark County Deed Book 7:283.

19. Clark County Deed Book 7:282. These properties of John Holder, deceased, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1799. The buyers were Robert Clark Jr. and Matthew Patton, who both died before a deed was issued to Jonathan Bush in 1806.

20. George F. Doyle, Clark County Tombstone Records (1935).

21. Weathering on the stone made 4s look like 1s. The “1814” date for the marriage actually looks like 1811 on the stone, but Doyle had previously transcribed the Clark County marriage records and knew that Jonathan and Diana were married in 1814.

22. Clark County Order Book 4:194, 321.

23. A wagon road was not needed for the Martin-Holder mill. Patrons brought their sacks of corn to the mill on horseback.

24. Winchester Sun, September 13, 1923.

25. U.S. Census, 1860, Clark County, Kentucky.

26. A copy of Mrs. Coffman’s letter and photographs dated 1926 were sent to Clare Sipple by Bush descendant, Elizabeth Wills.

27. Stephen Holladay, Revolutionary War pension application, S. 15459, VA; Clark County tax list #2, 1801.

28. U.S. Manufacturers Census, 1850, Clark County, Kentucky.

29. Winchester Chronicle, October 7, 1858.

30. Clark County Deed Book 42:310; 45:593; 58:66; 75:313; 77:122.

|

|

|